Plasmoids Wreak Havoc in Tornado Alley!

October 24, 2008

CONTENTS

TORNADO ELECTROMAGNETISM DENIAL

TORNADOES AS PLASMA STREAMS

To some, the title above might sound like science fiction. But evidence has been accumulating that tornadoes might easily be described as plasma streams. What's more, tornadoes might be preventable.

Tornadoes occur on every continent except Antarctica, and in every state of the US. Scientists have been puzzled by their behavior since ancient times. Lucretius, writing in De Rerum Natura (circa 60 BC), mentions the phenomenon, and gets the credit for being the first to suggest in writing that tornadoes and lightning might be related.

O then and there that wind, a whirlwind now, deep in the belly of the cloud spins round in narrow confines, and sharpens there inside in glowing furnaces the thunderbolt.

Of course, this was written before lightning was well-understood, and Lucretius' musings, to the modern reader, sound a bit like a child attempting to explain something to another child when grown-ups aren't around. But we shouldn't dismiss Lucretius off-hand — he may have been closer to an accurate description of the phenomenon than modern meteorologists.

VORTEX MODEL

The modern "explanation" for the formation of tornadoes can be summarized as follows, from a National Weather Service publication.

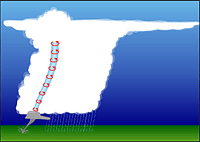

Stage 1: Before thunderstorms develop, a change in wind direction and an increase in wind speed with increasing height creates an invisible, horizontal spinning effect in the lower atmosphere.

Stage 2: Rising air within the thunderstorm updraft tilts the rotating air from horizontal to vertical.

Stage 3: An area of rotation, 2-6 miles wide, now extends through much of the storm. Most strong and violent tornadoes form within this area of strong rotation.

Hey wait — how did we get from Stage 2 to Stage 3? Well, once the vertical-axis rotation has been initiated, some of the literature suggests that the speed of the rotation gets increased as the vortex is stretched in length. Stretching the vortex makes it narrower, and the conservation of angular momentum makes the smaller vortex rotate faster. The faster-rotating vortex then accelerates more air around it, so it gets wider again, still spinning at the faster rate. I guess if you stretch it even more, it will spin even faster, and then become even wider. Pretty neat trick, actually.

VORTEX MODEL PROLEMS

While this "explanation" seems plausible enough on first glance, it's actually a few fries short of a physics happy meal. Streamwise vortexes, such as utilized by this construct, do not actually have any internal power that they can use to accelerate a far larger body of air. And while "vortex stretching" can increase the radial velocity of a vortex, it's not because the thing is being stretched like a rubber band, and getting narrower as a result, and where the conservation of angular momentum then increases the number of revolutions in a given period of time. It's because whatever is doing the stretching is lowering the pressure inside the vortex, and it's the lower pressure that tightens the radius. An updraft pushing the vortex up isn't going to supply the low pressure inside the vortex to do this.

And nothing in the construct even begins to explain the properties of tornadoes. Even if the powerful updraft in a supercell thunderstorm could generate a low-pressure vortex underneath it, the vortex wouldn't be able to do any damage on the ground. Low-pressure vortexes get weaker as the distance from the source of the low pressure increases. When encountering obstacles such as buildings and cars, such vortexes simply reorganize elsewhere — they don't push the obstacles out of the way. It takes a vortex with the size and power of a tropical cyclone to push stuff out of the way with thermodynamics. A supercell thunderstorm has nowhere near the energy of a tropical cyclone, yet a supercell has faster wind speeds. This means that we're missing something fundamental in our understanding of these storms.

In all due fairness to meteorologists, they do confess that they really don't understand what causes tornadoes. Here's a quote from a web page maintained by the Storm Prediction Center:

How do tornadoes form? The classic answer — "warm moist Gulf air meets cold Canadian air and dry air from the Rockies" — is a gross oversimplification. Many thunderstorms form under those conditions (near warm fronts, cold fronts and drylines respectively), which never even come close to producing tornadoes. Even when the large-scale environment is extremely favorable for tornadic thunderstorms, as in an SPC "High Risk" outlook, not every thunderstorm spawns a tornado. The truth is that we don't fully understand.

OK, that's fine. But in the absence of understanding, and under pressure from the general public to demonstrate the principles of the phenomenon, the publication of intuitively appealing "explanations" that don't actually work is not exactly respectable scientific practice. Besides, if you do this, then one day, when the true nature of the phenomenon becomes known, then you'll have to say, "Guess what — I lied. Here's how it actually works. The old explanation was just something that we thought you'd believe until we found the real answer." So who is going to believe you then?

TORNADO ELECTROMAGNETISM DENIAL

But that's not the big problem. When asked if there are electromagnetic explanations for the development of tornadoes, here's the dismissal from the National Severe Storms Laboratory:

As far as scientists understand, tornadoes are formed and sustained by a purely thermodynamic process. As a result, their research efforts are towards that end. They have spent a lot of time modeling the formation of a tornado and measuring many parameters in and around a tornado when it is forming and going through its life cycle. They have not seen any evidence to support magnetism or electricity playing a role.

How exactly do you get from "we don't know" all the way over to "we know it's not that"? The thermodynamic models of supercell thunderstorms and tornadoes are riddled with anomalies. Working with theories that leave anomalies on the table is part of scientific life, but when inadequate theories become so widely accepted that they start precluding alternate strategies, that's not science. Science is progress, or it's not science. It may be technology, and it may be credible, and it may make money. But what is already known is not the domain of scientists. Rather, what is not known is the pursuit of scientific enquiry, and new ways of thinking are the bread and butter of good science.

ELECTRIC TORNADO MODELS

The pursuit for the true nature of tornadoes has led some researchers to start entertaining ideas that aren't on the standard list. Peter Thomson, Wallace Luchuk, Tom Dehel, and the present author, to name a few, have been looking into the possibility that tornadoes are, in fact, electromagnetic in nature. Consider the following specimen.

Thermodynamics can partially explain the white funnel descending from the cloud above, as a low-pressure free vortex. But how are we going to explain the consistent-diameter sheath nearer the ground? And using only low pressure, how are we going to explain the large amount of material being stirred up at the ground level, without being drawn into the vortex?

CHARGE STREAM FROM GROUND

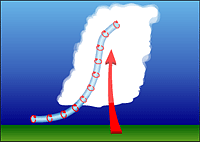

The only way to get a complete description of the phenomena is with a construct that includes a charge stream traveling from the ground to the cloud. This yields the following properties.

The rotation of the vortex is accentuated by the magnetic field generated by the charge stream. As a result, the vortex is rotating faster than it has a right to be, given the amount of inflow. This explains how a large volume of material can be stirred up at the ground level, without being drawn into the vortex. Because of high angular velocities and relatively low inflow velocities, the larger particles are being centrifuged out of the vortex at the entry point.

The lower sheath is caused by the presence of ferrous and/or ferric oxide particles, which are magnetically responsive, and therefore are captured by the magnetic field around the charge stream.

The complete list of properties of supercell thunderstorms and tornadoes that can be explained within the new electromagnetic construct is way outside the scope of this article. So is the really cool part — explaining how a toroidal plasmoid in the cloud can generate the electrostatic potential necessary for the creation of such a charge stream, without creating lightning instead. But the best part is that this construct opens up the possibility that tornadoes might be preventable. If tornadoes are, in fact, electromagnetic, then it might be possible to discharge the potential that is driving the tornado by triggering lightning strikes.

Sounds crazy, I know, but then so did the idea of sending a man to the Moon when it was first proposed. Good scientists just follow the physics, and that's all we're doing here. Everyone else will catch up at their own pace.

Charles Chandler

Charles Chandler is a software consultant and a natural philosopher living in Baltimore, Maryland.